The Memory War: On Vengeance, Identity, and the Middle Eastern Ledger

What the West Forgets, the Middle East Records in Full

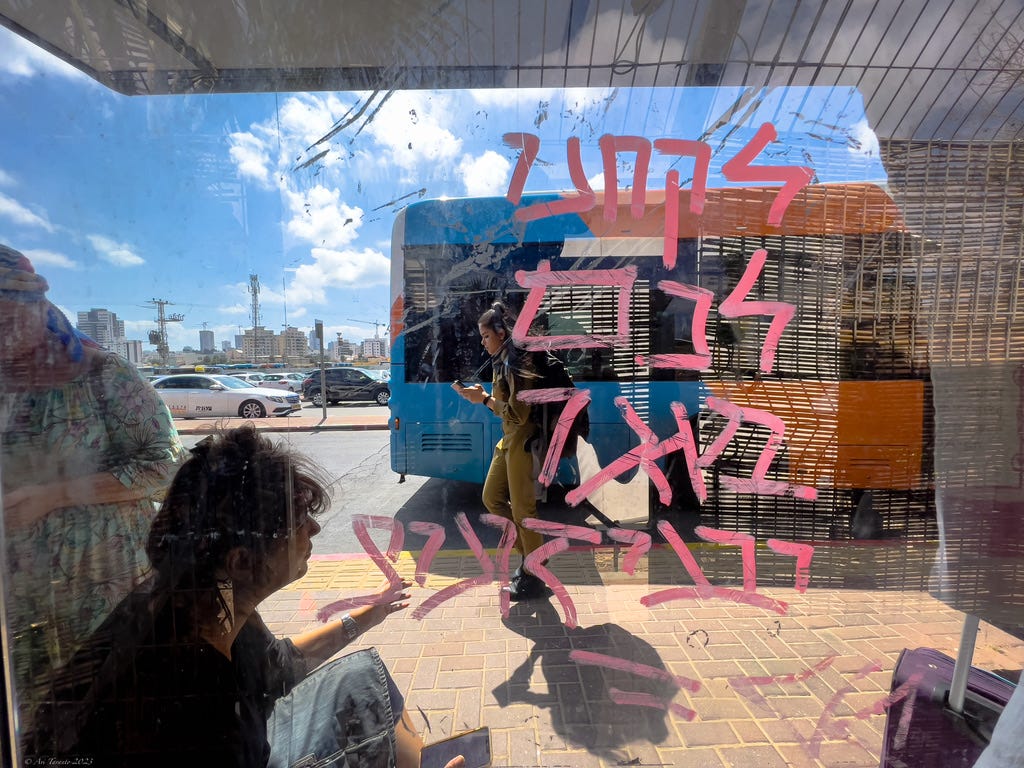

Welcome to the Middle East

Memory as Law

There was a genius in early Islam that has gone strangely unremarked in modern discourse. Not the revelation of God’s oneness, not the insistence on the Prophet’s station, but something quieter and arguably more transformative for the tribal world into which it was born: it offered a release valve for vengeance.

Where once the death of a tribesman meant endless retaliation—eye for eye, cousin for cousin, generation after generation—Islam introduced the concept of diya, blood money. Not forgiveness exactly, but containment. A new framework that didn’t erase memory or insult, but allowed both to be accounted for in a form that preserved dignity without demanding annihilation.

This was not a moral innovation. It was a memetic one.

The Arabian Peninsula had long been ruled by memory—long, durable, tribal memory. Everyone knew who killed whom. The roll of debts and betrayals was passed down like scripture, and to forget it was to dishonor your lineage. Islam didn’t erase that ledger. It formalized it. Diya offered a structured way out of the spiral, but not out of the logic. Vengeance remained sacred. It simply became negotiable.

This memetic structure didn’t stay within Arabia. It diffused outward and took root across the entire region. In different flavors, it became a cultural constant. Turks remember. Persians remember. Kurds remember. Druze, Azeris, Circassians, Baloch, Berbers.

And Jews.

Especially Jews who came from Arab lands.

Jews of the Region

It’s one of the strangest things to explain to Westerners—that the memory logic of the Middle East is not an aberration, not extremism, but the default setting. What varies is the degree of containment, not the presence of memory. To betray someone here is not to violate a temporary agreement. It is to tattoo your name onto their family's internal register.

This memory has teeth.

It outlives regimes.

It skips no generation.

It may lie dormant, but it is never erased.

The Jews of the Middle East absorbed this logic completely. More accurately, they helped co-create it. And while their Arab neighbors eventually forced them out—physically, linguistically, even conceptually—the memetic infrastructure remained intact.

That’s what no one in the West seems to understand. The Ashkenazi elite who built the modern State of Israel had a foot in Europe and a head in ancient Judea, but half the country was drawn from Baghdadis, Yemenites, Moroccans, Libyans, Iranians. People whose sense of history was never linear and whose capacity for cultural synthesis was born of exile, trade, and war. People whose memories were long. Who didn’t forgive. Who remembered the betrayal.

Arab Nationalism's Design Flaw

Arab nationalism did not begin with Muslims. It was, ironically, born of Christian fear. Throughout the Ottoman and post-Ottoman Arab world, Christian minorities worried that any emerging indigenous nationalism would be conflated with Islam. To avoid this—and preserve their stake in the future—they sought to craft a unifying ideology grounded not in faith, but in language. Arabic, rather than Islam, would be the anchor.

This was not an unreasonable instinct. A shared language, after all, offered a membrane of belonging broad enough to encompass diverse faiths. But the experiment had limits. Once Jews were brutally ejected from the Arab nationalist equation—socially, economically, physically—the only viable players left were Muslims and Christians. Other minorities like the Druze and Samaritans, while ancient and deeply embedded in the regional fabric, were too few or too reticent to define the framework.

Thus, Arab nationalism—though birthed in fear and designed for inclusion—wound up being structurally exclusive.

The Arab nationalisms that arose in the same period followed a different trajectory. They were reactions to Ottoman decline and Western imperialism, and they needed an internal glue. That glue was language. Arabic became the axis of identity. Not ethnicity. Not religion. Arabic. To be Arab was to speak the language, to inhabit its literary memory, to be part of the imagined continuity from Jahiliyyah to Nasser.

And for a time, Jews were part of that equation. They were Arabs. Native speakers. Merchants. Doctors. Neighbors.

Until they weren’t.

Arab nationalism proved brittle in its pluralism. Jews were first tolerated, then mistrusted, then expelled. Not just from countries, but from the category “Arab.” Their identities were retroactively rewritten. They became outsiders in lands they had inhabited for centuries.

And yet: the cultural imprint remained.

The Zionist Reboot

Unlike most national movements, Zionism was not born on the soil it claimed. It arose in Europe—secular, intellectual, romantic—and saw itself as a modern solution to an ancient curse.

But it was never at home in Europe. Jews were always marked as alien. Even when fluent in the local idiom, they were coded as Semites—near, but not quite; tolerated, but never of.

Zionism internalized this. It turned east not just physically, but spiritually. Its goal was not merely return, but reorientation. A purging of the diaspora self. A rejection of European fragility. A rebirth through labor, land, and language.

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda didn’t just revive Hebrew—he purged it of European loanwords and seeded it with Arabic and Aramaic. Zionism may have been born in Europe, but it loathed its upbringing.

It is precisely this dynamic—European in formation, anti-European in aspiration—that confuses the outside observer. Zionism did not elevate a vernacular peasant culture like Czech or Serbian nationalism. It had no native cuisine, no folk dress, no unified dialect to enshrine. Its people were too scattered, too hybridized, too literate to play the Ruritanian role.

So it built from scratch. And when it encountered Arabic culture, it did what cultures always do: it borrowed, blended, absorbed. Not cynically. Not as theft. But as necessity.

Return by Expulsion

What Zionism had to construct, Mizrahi Jews already embodied. Memory structures. Honor codes. Culinary intuitions. Rhythms of speech and survival. These weren’t European imports. They were native to the region.

When Arab Jews were ejected and found refuge in Israel, they didn’t become Europeans. They became Israelis—and brought the Middle East with them.

The irony is that Israel became a Middle Eastern state by absorbing those it did not initially center. And over time, Mizrahi culture stopped being peripheral. It became normative. Today, most Israelis have at least some Mizrahi blood. The cadence of the country is Levantine. Even the elite can’t fully pretend otherwise.

Today, Israeli food is hummus and zhug, laffa and kubbeh, shakshuka and sabikh. The street signs are in Hebrew but the curse words are in Arabic. The memory structure is tribal. The feuds are personal. The vendettas are tracked.

This is not Geneva.

It is not Brussels.

It is not Berkeley.

It is the Middle East. And it functions accordingly.

That’s what makes the accusation of Israel as a “white settler colonial state” so laughable. It’s projection masquerading as analysis.

Half the country’s Jews were kicked out of the Arab world. Many came barefoot, stripped of assets, traumatized, and told they no longer belonged to the civilization that raised them. They arrived in Israel and were told, again, to assimilate. To be sabras. To suppress their accents. To eat European food.

They did what they were told.

And then, slowly, they did what they remembered.

The Ledger Lives

Israel, meanwhile, went on building. Ejected from Arabness, Mizrahi Jews did not shed their cultural sensibilities—they adapted them, shaped them into something new. Israelis may have inherited the architecture of Arab nationalism—national revival, linguistic centrality, anti-colonial posture—but the structure they built with it exceeds anything that movement envisioned.

There is no easy metric for this. But the evidence is there in the baffled awe of the Arab Gulf. These are elites raised on courtly subtlety, poetic insinuation, and diplomatic flourish. They read between the lines with a fluency that Israelis tend to bulldoze right through. Where Gulf discourse is high-context and symbolic, Israeli memetic culture is brash, blunt, and literal. This makes Israelis clumsy guests at the regional table—but also undeniable.

The derision Israel receives today from the Arab elite is no longer propagandistic. It is admiring, begrudging, startled by just how free a people can become when they are cut loose from the obligations of fitting in.

That ejection hurt.

But it also cleared space for something generative.

It is no accident that Hebrew, long dormant as a spoken language, became the central current of Israeli identity. Nor is it incidental that Modern Hebrew feels odd to native speakers of the languages it borrows from—French, Russian, Arabic, English—because it Hebraicizes everything. The language doesn't assimilate words; it transforms them.

And yet, somehow, it’s fun. Playful. People who try learning Hebrew often remark—once they get past the steep beginning—that it’s deeply satisfying to speak. The grammar is crisp. The roots evoke ancient echoes. Syntax recalls biblical rhythm. And yet it operates seamlessly in coding bootcamps, startups, street slang, and battle commands.

This language is not just a tool of communication—it is a crystallized emblem of the broader memetic shift: continuity without mimicry, tradition without rigidity, a future built not on forgetting but on transmutation.

A Schema for the Stubborn

The past two years have made this unmistakably clear. While much of the West agonizes over definitions—who is oppressed, who is white, who is colonizer, who is victim—Israel has operated under a simpler, older logic:

We know who harmed us.

And we remember.

The list of names is long. Nasrallah. Sinwar. Deif. Haniyeh. The Radwan commanders. Iran’s entire top military echelon. The planners of October 7th. The heads of the IRGC. The financiers. The logisticians.

Some are dead.

Some are in hiding.

Some are waiting for their moment.

But the memory is intact.

This isn’t vengeance in the Hollywood sense.

It isn’t even always personal.

It’s cultural.

Civilizational.

It is the function of a people who have survived by tracking betrayal, by knowing who to trust, by keeping the ledger open until justice—or something like it—is delivered.

The Western gaze misreads all of this. It wants neat categories. Settler and native. White and brown. Colonizer and colonized.

But these binaries don’t map onto the Middle East. They obscure more than they reveal. They confuse geography with genealogy, religion with race, diaspora with privilege.

To say Israelis are “white” is to erase the Arabness that both Jews and non-Jews in the region recognize—whether they admit it or not. It’s to pretend that a Yemeni Jew is the same as a French one. That an Iranian Jew expelled after 1979 is interchangeable with a Litvak refugee. That someone whose grandmother speaks Judeo-Arabic is more like a Belgian than a Beiruti.

This is not only wrong.

It’s delusional.

So let’s leave it unsaid, but not unshown.

If you must reach for a simplification—if you absolutely require a schema to work with—then stop thinking of Israelis as Europeans.

Think of us instead as Jewish Arabs:

Arabs who were expelled.

Who reshaped ourselves.

Who refused to forget.

Arabs who no longer bear the name,

but still carry the structure.

We are not the same as our neighbors.

But we are of them.

And they know it.

And in ways both hostile and familiar,

they act accordingly.

No one forgets.

Everyone remembers.

And in this part of the world, that means everything.